There seems to be a growing chorus of economists making the claim that the Federal Reserve’s policy of quantitative tightening (QT) is a mistake. And regardless of their reasoning or their political persuasion, they may be right.

One of the reasons Ben Bernanke engaged in quantitative easing (QE) as a Fed Chairman but never in QT was because of his views of the history of the Great Depression. Like many Fed officials he tended to overlook the Fed’s role in creating the economic conditions that caused the Depression, i.e. the asset bubble that burst in 1929.

Instead, Bernanke focused on the Fed’s subsequent actions, which in his view drew liquidity out of the financial system and made an already bad crisis even worse. Could the Fed be repeating the same mistake today?

What the Fed Has Done and Is Doing

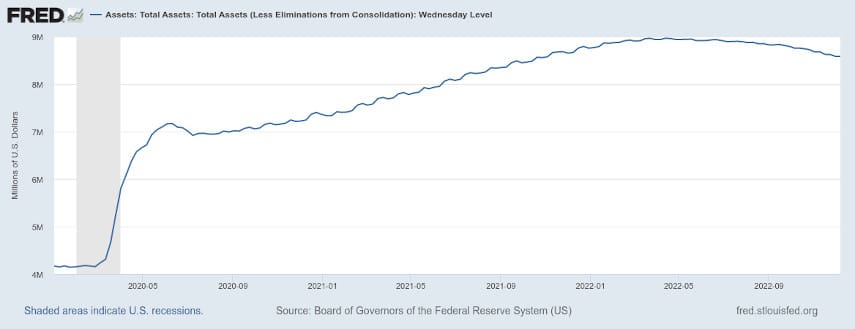

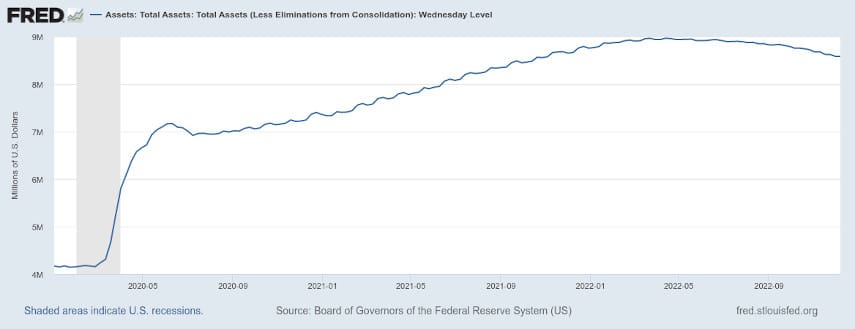

Let’s take a look first at what the Fed has done in the past 2-3 years and what the Fed is doing today. At the beginning of 2020 the Fed’s balance sheet held $4.173 trillion in total assets. But as COVID lockdowns began taking their toll on the economy, and as the federal government began to pass trillions of dollars in stimulus spending, issuing new debt to finance that spending, the Fed began to monetize that debt.

On February 26, 2020 the Fed’s balance sheet was still only at $4.158 trillion. But by June 3rd it had increased to $7.165 trillion, a $3 trillion increase in only three months. Over $2 trillion of this was due to an increase in securities holdings, with over $1.6 trillion in newly purchased Treasury securities and over $450 billion in newly purchased mortgage-backed securities.

The Fed continued to add to its balance sheet, so that by the end of 2021 it totaled $8.757 trillion, and peaked in April 2022 at $8.965 trillion. This was a massive increase in the size of its balance sheet, more than doubling it from its pre-2020 levels.

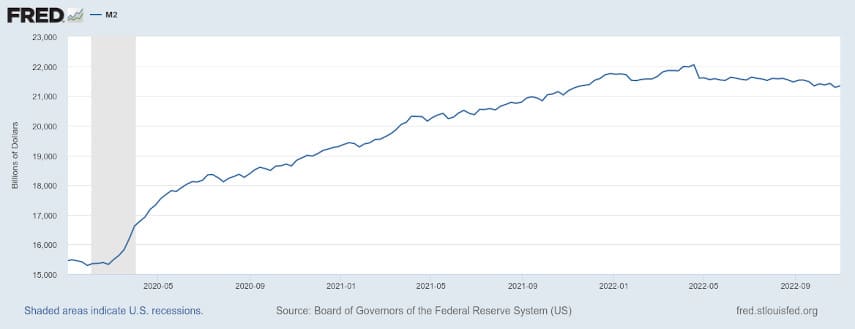

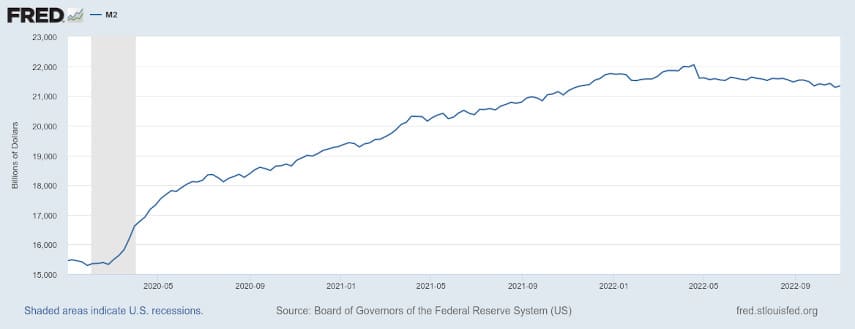

The result of this was a massive increase in the money supply, from $15.328 trillion of M2 on February 24, 2020 to $17.915 trillion on June 1, 2020. This was a 17% increase in just three months. M2 continued to climb, peaking at $22.052 trillion on April 18, 2022, a 44% increase from February 2020 and an 18% annualized rate of growth.

During that same period (2/20 to 4/22), the consumer price index only rose a total of 11%. So while the rise in consumer prices was certainly expected as a result of the increase in the money supply, consumer prices haven’t risen nearly as much as the money supply.

Even though the money supply has started to contract slightly, and the inflation rate has slowed, it is not unreasonable to expect inflation to continue rising to try to catch up with the increase in the money supply. After all, monetary policy always operates with a lag, and it took about a year for the large increases in M2 to make themselves felt in CPI.

What the Fed is trying to do is to get ahead of the curve. By engaging in QT and attempting to reduce the size of its balance sheet, it is trying to bring the money supply down before CPI fully catches up with previous money supply increases. But there’s a risk to doing that.

Monetary Policy and the Business Cycle

The problem with monetary policy is that it has real effects on the economy. Central bankers today, however, believe in the neutrality of money. That is to say, they believe that changes to the money supply may have short-run effects on the economy, in the long run monetary policy doesn’t affect the structure of the economy.

This runs counter to the Austrian theory of the business cycle, which sought to explain why businessmen who successfully ran businesses suddenly made major mistakes which led to financial crises, and seemingly all at the same time. Austrian business cycle theory (ABCT) explains how money is not neutral, neither in the long run nor in the short run.

Manipulating the interest rate as central banks do is manipulating one of the core prices in the economy, the price of money (or time, depending on which theory of interest you subscribe to.) This manipulation of interest rates alters the structure of production in such a way that the economy is affected in the long run.

Lowering interest rates makes long-term, capital intensive projects seem cheaper than they otherwise would be. Projects that might not be profitable at 8% interest rates might be profitable at 3% interest rates. Businesses undertake these projects with the expectation of future profitability.

In an economy without monetary manipulation, lower interest rates would be the result of increased savings, as consumers defer present consumption in order to consume more in the future. These increased savings depress interest rates, as more funds are available to lend.

But when central banks force interest rates down artificially, it sends the signal that consumers are saving even when they aren’t. So when the long-term projects that are stimulated by these low interest rates are completed, consumers are tapped out because they haven’t been saving.

You need only look at charts for personal savings rates and interest rates to realize that the combination of low interest rates and low savings rates is ultimately unsustainable. What happens is that when these long-term projects are completed, and consumer demand isn’t there, the resources that have been misdirected or malinvested into these projects need to be liquidated and put to use elsewhere.

This is the bursting of the bubble with which we’re all familiar. Companies scale back, lay off employees, recession ensues, and the recovery occurs when the resources that were malinvested are put to more productive use. This is the Austrian explanation for the booms and busts of the business cycle. It explains how monetary expansion causes the business cycle. But what about monetary contraction?

Monetary contraction is less well studied because it just doesn’t happen that often. Look at money supply figures and you’ll see that the long-term trend is for the money supply to increase. There has never been a sustained decrease in the money supply… until now.

We’ll have to wait and see just how long the Fed sticks to its monetary tightening, and whether it pivots back to monetary easing, but if it sticks to its guns and continues tightening monetary policy for the next few months or years, it will provide an interesting look into what QT does. And unfortunately, QT could end up being just as dangerous as QE.

Don’t Just Do Something… Stand There!

If monetary easing causes changes to the structure of production then it follows logically that monetary tightening will do the same. But it won’t necessarily just reverse the damage that was done through monetary easing. It could be an entirely new industry or set of companies that ends up being harmed.

The bias towards action means that the Fed is going to do something, anything. But because both monetary easing and tightening can be damaging, no matter what the Fed does it is going to cause harm. The best course of action would be do allow inflation to run its course, not add any more to the money supply, and deal with the effects.

Instead, the Fed is actively tightening the money supply, something it last did in the 1930s. And with the blame the Fed got for making the Depression worse in the ‘30s, the Fed’s track record on monetary tightening isn’t exactly good.

We have to hope that the Fed isn’t going to overtighten and end up making a coming recession even worse. But given the lag in monetary policy, both in how long it takes for monetary policy changes to take effect and for how long it takes for the Fed to recognize the consequences of its actions, that’s isn’t a certainty.

Remember that it took the Fed months before it acknowledged that inflation was even happening. And even after that it continued adding assets to its balance sheet for months before deciding that it would finally try to start tightening monetary policy. So how long would it take for the Fed to acknowledge that its fight against inflation is bearing fruit? Would it stop its tightening too late and make things worse for the economy?

Protecting Your Wealth

If you’re nervous about the economy and worried about how you can trust a handful of unelected bureaucrats to manage things, you’re not alone. Millions of Americans are in the same boat, and many of them are already starting to take steps to protect themselves against the likelihood of an upcoming recession. Many are doing so by buying gold and silver.

Gold and silver have served as safe havens and stores of value for centuries, protecting wealth through both good times and bad. Their reputation is established, and their performance during periods of economic turmoil in recent decades has been remarkable. During the stagflation of the 1970s, for instance, both gold and silver’s annualized gains were over 30% over the course of the decade. And in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, gold nearly tripled in price while silver more than quintupled.

Many investors today are hoping that gold and silver will repeat those types of performances. And they’re turning to gold IRAs and silver IRAs as one method of protecting their savings and investments with gold and silver.

If you’re worried about the future and looking to protect your savings and investments, now is the time to start thinking about how you’re going to do that. Call the experts at Goldco today to learn more about how a gold IRA or silver IRA can help you.